Is Sub Saharan Africa Primed and Ready for Explosive Growth?In the news world, financial-business world, and the development world, there is lately a renewed and strong interest in the idea of “Investing in Africa,” whether through venture capitalism, private equity, or through public market exchanges. Indicators I have seen of this trend include magazine articles, books, blogs, websites, SRI material and other investment prospectives, business and development conferences, and even a documentary that honing in on the subject.

Why the sudden and new interest? Some claim the disillusioning recession in the U.S. and elsewhere and the ostensible saturation of other markets is turning the attention of investors on Africa as an investment target. Certain shining examples of companies in such growth industries as precious minerals, banking, and cellular service across sub-Saharan Africa helps to turn these gazes. I think also that African markets are becoming more accessible, or at least feel closer and more important, to investors: African exports are feeding the “emerging economies,” new stock exchanges are slowly opening across Africa, and—as I read recently in the Financial Times—several African countries are trying to get a number of Africa-owned companies listed on the Chicago Stock Exchange. As a final possible factor to the recent attention, though“Socially Responsible Investing” rightly has plenty of critics, no one can deny also that the very idea of “Investment in Africa” is an admittedly more sexy one that buying stocks in your typical Dow-Jones company.

A Good Thing?

My very cursory understanding of developmental growth theory economics tells me that this buzz of investment interest, if materialized, could be very good, because the “I” variable (Investment) is one of the most—if not the most—necessary variable for macroeconomic growth. Big financial investments are also necessary (though not sufficient) for long-term poverty alleviation, as jobs, assets, productivity, and government revenue for social programs (through taxes) are all generated. When the end-consumer is the poor person himself, he or she can also be empowered by being offered a newer or cheaper product to improve his or her quality of life (This argument is advanced in Profit from the Bottom of the Pyramid). Sometimes these suddenly accessible “consumer products” are as essential as small loans or reliable ambulance services.

On the investor side of things, prospects are also good…very good in fact with potential returns marketed at twenty-some percent. Africa represents to many investors an environment perhaps poor in material assets rich in land and natural resources, labor, entrepreneurship, and a potential consumer base, and so primed for explosive growth so long as one can identify those good targets to inject the funds.

And “so long as…” remains the biggest potential barrier to this kind of profitable and sustainable investing. Africa is a rich and varied continent…investors cannot afford to categorize it as one place; rather, they must specify their research and understanding of a country’s realities and economy. Certain crucial factors of investment climate must be well analyzed such as trends related to infrastructure developments, corruption, rule of and respect for private property and commercial laws, taxation, and political and social stability. If not, one may be likely either to see the whole region of Sub-Saharan Africa as a continent of genocide, civil war, and election fraud. Or else, one is likely to commit the opposite error by actually investing in a Darfur, a Northeastern Congo, a Zimbabwe, or some other place more likely to erupt in some mass social disruption than in economic growth. This error happens by forgoing deference to the complex histories and varied difficulties that characterize many African countries.

America is suffering at this moment the fallout from the bursting of a particular financial market bubble that was based on irresponsible and unregulated risk. The last thing the world—and especially Africans— needs now is another mass financial venture that is a powder keg in disguise.

Is Bénin a Ripe and Risk-Minimal Market for Investment?Given the potential benefits, along with the appropriate risk assessment that must happen, could Benin make a good target should the region see a financial investment windfall? I think so.

On the risk side of things, Benin is about as stable as you could get in the region: There has not been severe civil disruption for almost 20 years (see the Onion article satirical affirmation of this fact) and has enjoyed free and fair elections since then. There are also no outstanding ethnic, political, or resource-driven issues that have driven other African countries to war and unrest. Benin has no extremely lucrative resources that might attract corrupt leadership or render other exports too expensive to develop. The itinerant president, Yayi Boni is widely supported and has made it one of his primary goals to stem corruption. Evidence of this includes Benin’s election by the U.S. as a beneficiary of the much-prized (but hard-to-get) aid from the Bush’s Millinium Challenge Corporation. Among other things the MCC project is expanding and cleaning up Cotonou’s international port, once infamous for its corruption. Such are some of the indicators and evidendences that Benin may be a healthy environment for a large investment, especially when compared to other countries of the region.

If Benin were indeed poised for explosive growth, here is my estimation of the potential profitable sectors into which investors could inject their confidence, ideas, and inflow of private capital:

Transportation. There is the need and market here for car-taxis to service city populations, bus lines to serve the cross-country travelers, and possibly also a rail service to run over Benin’s largely unused railway line.

Tourism. Benin’s beaches, wildlife parks, and varied cultural landscapes are beautiful, but remain unknown to tourists…what’s needed is marketing and a more developed tourism infrastructure of hotels, touring agencies, etc. to exploit this possibility. Holding company Dubai World entered into negotiations earlier this year to develop beachfront, hotels, and game parks in the South.

Communications. Perhaps telecommunication but most especially internet, especially with the virtually untapped fiber optic line that runs through the country from the south to the north.

Banking Services. Perhaps in mortgages and micro-loans, as is taking place …across much of Africa.

Certain Agri-based products. Shea butter, cashews, and pineapples immediately come to mind, for which large and unsatisfied markets exist abroad.

Electrical Power. Most of Benin, derives its power from gas generators and is therefore electrically reliant on Nigeria. This source of energy is expensive and non-sustainable and will only become more so as oil prices increase with the demand for power. Alternative sources of energy could find an eager consumer base.

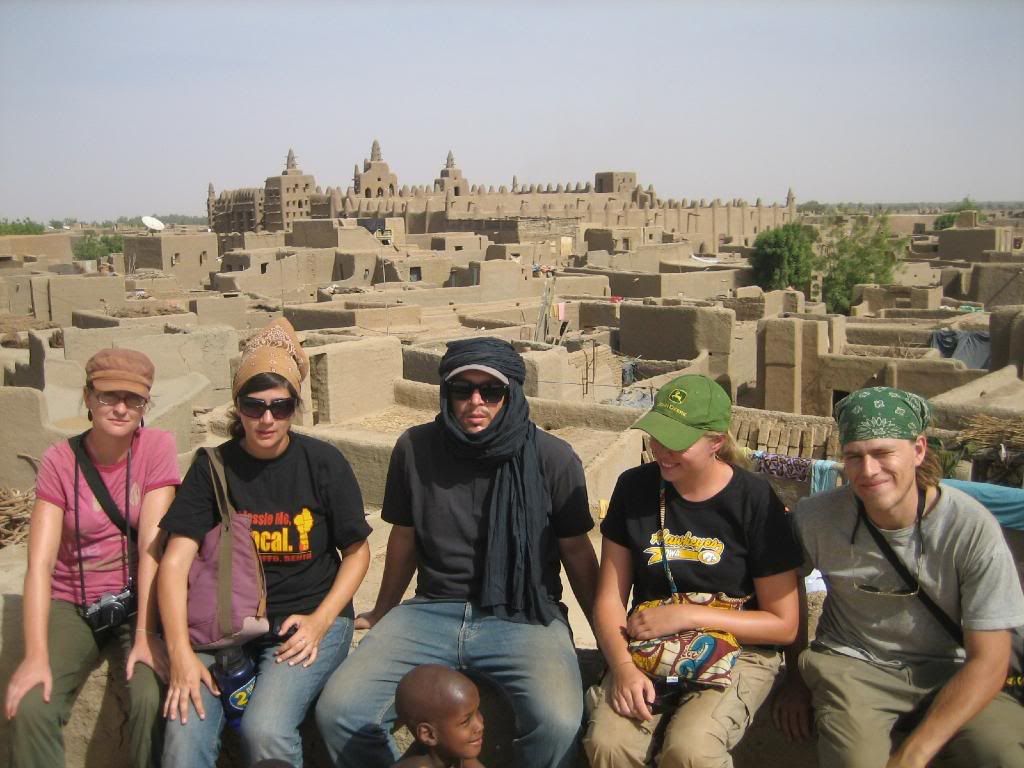

The world's largest mud mosque, seen through a house window in Djenne, Mali.

The world's largest mud mosque, seen through a house window in Djenne, Mali.